On 25 March, Emmanuel Macron invoked article 49.3 to bypass a parliamentary vote on widely-opposed pension reforms, effectively utilizing special powers to force through measures rejected by roughly two-thirds of the French electorate. Beyond the overt threat of centralizing executive powers and worsening an already-strained social crisis, Macron’s invocation of 49.3 raises the question of the apparent responsibility of elected representatives in liberal democracies. Does this responsibility rest in justifying and shaping their political program to their constituents or in enforcing the exigencies of creditors, debt-ledgers, and cheque books, even when they come into conflict with the popular will? Can financial rationale coexist with the principle of democratic sovereignty?

49.3 & macron’s todestrieb

Demonstration by French railway workers during the 1995 general strike

The pension system has long been a political flash-point in France, viewed not just as a cornerstone of the social security system but as a symbolic réussite of the dignity of labour dating back to the 1789 revolution. The last attempt to “reform” the scheme in 1995 triggered the largest general strike in recent memory. Given the unprecedented show of unity across what is normally a deeply divided labour and political scene, this round of confrontations is promising to match if not exceed the last in both intensity and length.

Yet, Macron’s decision bespeaks a more troubling irrationality in what is euphemistically termed ‘fiscal conservatism,’ i.e. neoliberalism and austerity. The choice to bypass parliamentary deliberation on an already divisive question of public policy less than a year after his narrow reelection and the loss of his absolute majority in parliament (by more than a symbolic margin of difference) will likely spell political self-destruction for Macron’s Renaissance (aka LREM). Macron himself has confessed to his reliance on the support of a social-democratic and left-wing ‘front républicain’ during the deuxième tour, which was presumably mobilized in large by the alternative prospect of a Le Pen presidency as opposed to any popular endorsement of Macron’s economic agenda (one only needs to be reminded of the broad public support behind the gilets jaunes in 2018, which peaked in December of that year during France’s most intense period of social unrest since Mai ’68). Macron’s administration only narrowly survived two votes of non-confidence the Monday following his invocation of 49.3 – votes that were made constitutionally possible by the very amendment enabling him to invoke special executive powers, the glaring irony of which cannot be overstated. What is more, assuming LREM’s defeat in the next round of elections, either prospective government will have likely positioned themselves in opposition to Macron’s neoliberal mandate – whether that proves to be la France Insoumise led by the hard-left enfant terrible Jean-Luc Melanchon or Marine Le Pen’s “post-fascist,” right-wing populist Rassemblement National (the rebranded and ostensibly ‘sanitized’ heir to her father’s overtly fascist Front National), assuming the long decay of France’s establishment political parties continues unabated. It wouldn’t be a far cry to predict that the very réforme des retraites triggering Macron’s downfall will be buried alongside him. All of which begs the question: is Macron simply practicing bad political strategy, or are there extra-political forces in play behind the mise-en-scène of political theatre collapsing en plein vue?

Declamations in the spirit of ‘Macron, président des riches,’ even ‘des ultra-riches,’ paint a picture of overt intentionality – even a conspiratorial intentionality – motivating his ‘deconstruction’ of France’s social security system. As politically effective as these cynical narratives may be to aggravate and mobilize popular dissent, the political situation traced in contours above betrays a more confounding reality than any straightforward confrontation of class interest or political ideologies can explain. What if Macron is honest when he claims that he is doing what is right – in other words, what is financially necessary (a necessity far from unilaterally accepted, even by the ‘experts‘ of the economy) – to “save” France’s social democracy, to the extent of committing political self-sacrifice?

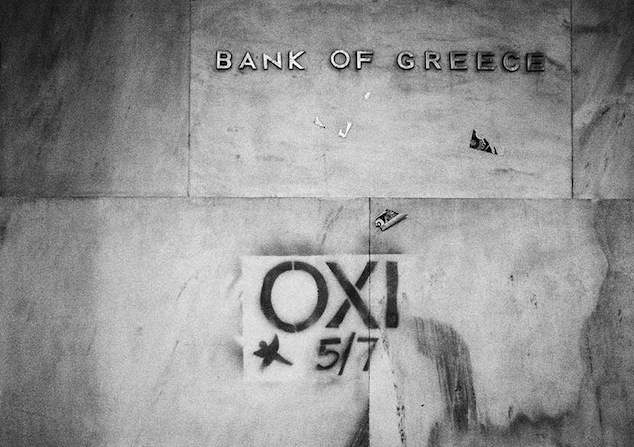

Reminiscent of far-left SYRIZA’s dismal retreat from the anti-austerity campaign that had dramatically catapulted the Greek party to power in 2015 amidst the worst years of the country’s sovereign debt crisis – followed by their equally dramatic fall from power and public grace in 2019 – the reasoning behind Macron’s decision to risk social and political upheaval in pursuit of “fiscal stability” testifies to the subterrene capacity of economic rationality to subvert and undermine democratic deliberation and popular will, despite also threatening the very political survival of those charged with enforcing it.

A Todestrieb at the heart of neoliberal political institutions. The repetition-compulsion of pure economic reason “that actually incites us to tear down all boundary posts and to lay claim to a wholly new territory that recognizes no demarcations anywhere […] that takes away these limits, that indeed bids us to overstep them” (Critique of Pure Reason 385-86).

mute compulsion & real abstraction

In the chapter on “so-called primitive accumulation” at the close of Capital I, during his description of the formative conditions of the capitalist mode of production in 18th-century England, Marx offers a peculiar formulation of the compelling necessity by which capitalist relations are inculcated into the lives and minds of the working class, beyond its ‘blood-soaked’ origin:

It is not enough that the conditions of labour are concentrated at one pole of society in the shape of capital, while at the other pole are grouped masses of men [sic] who have nothing to sell but their labour-power [i.e. class division doesn’t suffice to ‘make capitalism run’]. Nor is it enough that they are compelled to sell themselves voluntarily [i.e. capitalism cannot be explained by recourse to individual autonomy]. The advance of capitalist production develops a working class which […] looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self-evident natural laws. The organization of the capitalist process of production, once it is fully developed, breaks down all resistance […] The silent [or mute] compulsion of economic relations sets the seal on the domination of the capitalist over the worker. (Capital I 898)

The deceptively simple, compulsory sway of capitalist economic relations described above is thrown into relief against the background of the ‘subsumption processes’ of labour examined in the appendix to the first volume, its apparently unfinished last chapter. ‘Formal’ subsumption designates the top-down imposition of wage-labour on forms of work developed before the emergence of specifically capitalist relations of production, such as the absorption of agricultural work into the market, without fundamentally reorganizing the labour process itself. In this form, the extraction of surplus-value labour, or the value of commodities produced in excess of wages paid, is only ever ‘absolute’: it depends on the sheer extension of the working day beyond the compensated duration required to sustain the labourer. ‘Formal’ subsumption, Marx argues, is fundamentally precarious and inadequate to the demands of capital, since ‘absolute’ surplus-value quickly meets the natural limits of the worker. Either the owner of the means of production inhumanely extends the duration of labour, risking the exhaustion and likely death of workers or their self-organized resistance, as evinced by the earliest demands of the union movement for an 8-hour working-day; or the capitalist hires more workers, thus siphoning off capital from the profit-margin by paying higher aggregate wages.

By contrast, the ‘real’ variant of subsumption points to the recomposition of productive relations and the subsequent intensification of productive power according to the dictates of capital. Now, surplus value takes on a ‘relative’ form: by means of the reorganization of the division of labour by the introduction of ‘piecemeal work,’ or the development and introduction of new means of production, the efficiency of labour is increased and the extraction of surplus-value augmented without necessarily extending the duration of work itself. The ‘real’ subsumption of labour is the form proper to capitalism, emerging in tandem with the increasing geographical scale of the capitalist commodity-economy alongside the corollary demand on productivity and profitability – an expansive process of which we are living at the apex today with the globalization of capital. Without belabouring this fecund distinction, Marx observes that both forms of subsumption are driven by “a mode of compulsion not based on personal relations of domination and dependency, but simply on differing economic functions” (1021). Prima facie, this compulsion results from the division of society between those who control the means of production and, by extension, capital, and those who must sell their labour-power to survive. What the subsumption processes share, in other words, is an indirect form of economic compulsion over individuals. This is contrasted to the direct power exacted by sheer physical force or the coercive apparatuses of the state, most evident in chattel slavery or the expropriation of land and resources by colonialism, imperial conquest, and so on.

However, the ‘mute compulsion of economic relations’ cannot be explained away by class division or the nominally voluntary character of labour relations. It is necessary that the worker ‘looks upon the requirements of the capitalist mode of production as self-evident natural laws,’ that these requirements take on a quasi-objective status apart from the relation between the capitalist and the worker. With the mature development of capitalism, asymmetric relations of dependance and domination that had previously appeared as directly ‘personal’ or coercive now present themselves “as if they were natural conditions” uncontrolled by individuals. As if these individuals really were “ruled by abstractions” of objective economic laws and categories (Grundrisse 164). Such laws and categories, while necessitated by the capitalist mode of production, are the ‘theoretical,’ abstract expression of the ensemble of social and productive relations populating the economy. They become ‘objective’ or real not by virtue of representing to thought any spontaneous, natural laws or features of the world – as in the ‘abstract’ formulas of physics – but through the actual, ‘generalized‘ dispersion of social interdependency by the capitalist economy. That is to say that the expansive and centrifugal movement of capital, it’s ceaseless extension into new territories and penetration into society’s productive forces, distributes unequal relations of dependancy and domination in general. The immediate relation between a capitalist and their workforce is just a particular instantiation of the general domination of ‘dead’ over ‘living’ labour or the opposition between capital and labour. What ‘sets the seal’ on this universal relation of domination is the ‘objective’ and ‘necessary’ character of the demands of capitalism: the infinite demand of profit and the subsequently ceaseless expansion of surplus-value extraction, spurring a movement of seemingly limitless economic growth.

“Relations can be expressed, of course, only as ideas,” Marx explains, and the increasingly ubiquitous character of capitalist social relations corresponds to the degree of abstract generality adopted by their ideational expression. Hence, Marx’s retrieval of the abstract concept of labour forwarded by Adam Smith, with the critical caveat that this “abstraction of labour as such is not merely the mental product of a concrete totality of labourers […] but of historic relations,” since “the most general abstractions arise only in the midst of the richest possible concrete [social] development, where one thing appears as common to many, to all” (Grundrisse 104-5). Once a social relation is distributed in general, ‘it ceases to be thinkable in a particular form alone.’ The ‘abstract’ concept of human labour as such, without respect to its particular, ‘concrete’ form (e.g. as baking croissants, tilling fields, or teaching schoolchildren), emerged only once the individual could in principle move ‘freely’ between different kinds of work at will. That is, once labour as a valuable, value-generating social activity lost its ‘organic’ link with the social place of real individuals, unlike under feudalism or caste hierarchies.

The abstract form of economic relations attain effective reality through their necessitated and constrained performance on the market or in the workplace: “here, then, for the first time, the point of departure of modern economics, namely the abstraction of the category ‘labour’, ‘labour as such’, labour pure and simple, becomes true in practice” (Grundrisse 105). The same is true of any number of other ‘economic’ categories. Rather than expressing timeless truths of human nature or objective facts of the world apart from society, they are born out of the historical development of productive relations through which they attain effective, practical reality. In this way, economic abstractions are reproduced in practice while simultaneously reproducing the total ensemble of social relations which they express. Economic categories and laws are materially formative, while being generated by, or attaining real existence through, material practices.

To illustrate this difficult point with respect to the most ubiquitous economic ‘form,’ value, Marx offers a prescient, if imperfect, analogy in the first German edition of Capital. Where one commodity (e.g. 20 yards of linen) is said to express the value of the whole world of commodities, building up to his treatment of money as the ‘independent’ incarnation of value, he writes: “it is as if alongside and external to lions, tigers, rabbits, and all other actual animals […] there existed in addition the animal, the individual incarnation of the entire animal kingdom. Such a particular which contains within itself all really present species of the same entity is a universal (like animal, god, etc.)” (37). Feuerbach had once found in the Christian God an alienated projection of humanity’s flesh-and-blood ‘species-essence,’ the common quality shared by all real human individuals. Marx now finds the ‘value-essence’ of the world of commodities, that shared trait of being mutually valuable and hence exchangeable despite their real differences, externalized in the peculiar commodity of money, their ‘general equivalent.’ Money, as the general or universal expression of the value-character of commodities, hence appears to take on an existence as independently valuable ‘alongside and external to’ croissants, flour or houses. As if money were the transubstantiation of value as such, like the bread and wine of the Eucharist as the blood and body of Christ for christians. In other words, it appears as if the generic category, ‘animal,’ ‘value’ or ‘God,’ had a real, individual existence in the world. As if value were a specific difference, in other words, as opposed to merely expressing a shared trait among individual commodities. That is, a structural synecdoche of the capitalist mode of production.

However, this totum pro parte is not the result of a fallacy in thought, but is practically realized by our common activity. Through acts of exchange, value really is imbued to money. Qualitatively distinct commodities really are rendered commensurable and equal. On an expanded scale, collateralized debt obligations really do evict homeowners and lay-off workers, despite the fact that the latter cannot touch, let alone eat or drink, such financial instruments. These abstractions are first effected by our hands and not in our heads. This is the crux of the hotly-debated notion of ‘real abstraction‘ preoccupying much Marxian scholarship of late.

‘As if alongside and external to lions and tigers, there also existed the animal‘

Previously as hierarchy and servitude, now as private, autonomous individuals meeting one another as free equals on the market: Marx’s point is that the latter is an appearance effected by the generalized ‘fetishization’ or objectification of economic relations by capital, but a distorting appearance nonetheless. By elevating the abstract, formal equality of commodities effected by exchange to the appearance of equality among persons; by likewise elevating the free movement of capital on the market to the appearance of the free movement of individuals; what this form of appearance elides is precisely the really asymmetric power-relations and binding network of necessity engendered by capitalism. To quote Marx, “it is not individuals who are set free by free competition; it is, rather, capital which is set free“:

As long as production resting on capital is the necessary, […] the movement of individuals within the pure conditions of capital appears as their freedom […] Free competition is the real development of capital. By its means, what corresponds to the nature of capital is posited as external necessity for the individual capital; what corresponds to the concept of capital, is posited as external necessity for the mode of production founded on capital. The reciprocal compulsion which the capitals within it practise upon one another, on labour etc. (the competition among workers is only another form of the competition among capitals), is the free, at the same time the real development of wealth as capital […] The statement that, within free competition, the individuals, in following purely their private interest, realize the communal or rather the general interest means nothing other than that they collide with one another under the conditions of capitalist production, and hence that the impact between them is itself nothing more than the recreation of the conditions under which this interaction takes place. (Grundrisse 650-52)

‘Free competition’ thereby exercises a compelling necessity vis-à-vis the behaviour of individuals despite appearing from within as their very ‘freedom.’ In this way, capital reproduces its constitutive relations through the mutual behaviour or ‘collision‘ of individuals on the market. ‘Free competition’ comprises the countervailing tendencies of capital towards socialization, or the generalization of economic relations, and unsociability, or the ‘mutual attraction and repulsion’ of individuals. Where Kant had argued that the ‘unsocial sociability’ of humans was their natural disposition, Marx discovers that it is, in fact, a historical contradiction of capitalism. Human unsociability or competition, in other words, is a distinctly social fact, the fetishized ‘inverted world’ of the socialization of economic relations engendered by the compulsion of capital. And, unlike direct and personal forms of coercion, this compulsion is ‘mute’ or ‘impersonal’: it is posited as so many external laws to which individuals must conform rather than being a social dynamic that individuals collectively reproduce through their reciprocal, social activities.

The description of this general tendency as “mute compulsion” has received little attention before this year’s publication of Søren Mau’s eponymously-titled book, in which he convincingly situates this phrase – which only appears once in the published manuscripts of Marx’s later writings – at the heart of a Marxian theory of economic power, among the pantheon of other widely celebrated, critical concepts (e.g. exchange value, abstract labour, fetishism, ‘real’ and ‘formal’ subsumption, etc.). Mau argues that Marx had discovered a form of economic power emerging with the matured capitalist mode of production, one distinct from ideological or coercive power articulated by Durkheim, Althusser or Foucault. The compulsive character of this form of power lies in the compelling influence exerted on the behaviour of individuals and institutions alongside the ‘universal’ social compulsion or movement that it precipitates, determining the form of commodity production, the general distribution of social interdependency, and the organization of the political and civil life of society, resonating all the more today. Likewise, the “muteness” of this compulsion points to the salient fact that, under normal conditions, it functions in motu perpetuo, with apparently little need of extra-economic enforcement or intervention by the state. The motivating rationale of the market thereby adopts a seemingly autonomous movement over the heads and hands of individuals.

Macron claims that the réforme is necessary, that the proposals offered by his opponents are out of touch with reality, infeasible. “Necessity,” “feasibility” or “reality,” to be sure, lead existences outside the head of the President. As categories, they are engendered by the network of interdependency and the centrifugal tendency of markets set in motion by capitalism. However, these categories are far from being naturally given phenomena. They have a definite historical genesis and are reproduced by a specific form of economic power acting through individuals and institutions, workers and firms, or politicians and nations. In order to illustrate what this looks like today, we need to take a brief foray into finance.

real subsumption & fictitious capital

It goes something like this: the worker depends on the employer for wages in return for selling their power, the employer depends on liquid capital from investors to launch and sustain their business, investors depend on financial institutions to manage and securitize their investment portfolios, financial institutions depend on governmental and intergovernmental bodies to monitor and regulate capital flows, and so on. Viewed conversely, this binding dependancy also holds, albeit with a greater share in the balance of power inverse to risk exposure: financial institutions depend on investor profiles to maintain their competitive edge on credit markets, investors depend on dividends returned from their investment portfolios, the employer relies on the labour of their workers to sustain their quarterly profit margins. The centrifugal movement of capital, especially financial capital, necessarily distributes these relations of dependance in the most general sense. In other words, it socializes economic interdependency.

Once again, we are currently living at the apex of this expansive process. The global interconnection of finance and corresponding distribution of profit and risk through complex financial instruments have exceeded nearly every existing regulatory framework. Whole national economies, even unions thereof, have come to depend on foreign and multinational financial institutions bearing no direct responsibility to the population or government of any specific nation. Under normal circumstances, the complex network of necessity engendered by this expansive, seemingly totalizing process functions “mutely” in the background of our lives, while its real consequences only become apparent negatively, in camera obscura, through exceptional moments of crisis.

The burst of the American real-estate bubble in 2008 due to widely-fraudulent lending practices triggers a global domino effect, forcing Greece to default on its national debt. A homeowner in Sacramento County, California is evicted, a family in the Kolonos district of Athens collects food from the waste after both parents lose their public-sector jobs following severe austerity measures. Recovery from the Greek sovereign debt crisis extends to the present, while trading in synthetic derivatives remains common practice on the international credit market despite setting the world economy into a nearly-apocalyptic downfall 15 years ago.

Christian Marazzi describes the situation with clarity: “the abyss opened by derivative financial products seemed incommensurable. Public deficits increased within a few months to the levels of the Second World War, the geopolitical scenarios were being modified as needed and the crisis, instead of subduing, was inexorably expanding with its most devastating effects on employment, wages, and retirement. On the real lives of entire populations” (The Violence of Financial Capitalism 10). Likewise, Alberto Toscano and Brenna Bhandar write: “the processes of financialization animating the dynamics of the 2007–8 crisis involved the violent irruption into the everyday lives of millions of a panoply of ominous acronyms (ABSs, CDOs, SIVs, HFT, and so on), indices of highly mathematized strategies of profit extraction whose mechanics were often opaque to their own beneficiaries. At the same time, this process of financialization was articulated to the most seemingly ‘concrete’, ‘tangible’ and thus desirable [value] to the citizens of so-called advanced liberal democracies: the home” (Race, Real Estate and Real Abstraction 8).

“OXI!” [No!]: pro-‘GREXIT’ stencil on the Bank of Greece during the 2015 referendum

The 2009 UN report on the financial crisis opens with the following, ominous assessment: “market fundamentalist laissez-faire of the last 20 years has dramatically failed the test. Financial deregulation [i.e. liberalization of capital flows and privatization of returns] created the build-up of huge risky positions whose unwinding has pushed the global economy into a debt deflation [i.e. socialization of risks] that can only be countered by government debt inflation [i.e. socialization of costs …] The key objective of regulatory reform has to be the systematic weeding out of financial sophistication with no social return.” Yet, here we are again.

Such “financial sophistications” are nothing but synthetic expressions of the complex relations of interdependence in capitalism – most immediately as shares, bonds or debt obligations and at further remove, derivatives, credit default swaps or futures. Moreover, these financial instruments become sites of secondary profit-extraction: they are packaged and traded among investment banks, hedge-funds or other firms in esoteric, unregulated financial markets euphemistically termed the ‘shadow banking system.’ In the process, the original instruments are often divided into minutiae, interwoven, and recomposed before making their way back into ‘tertiary’ financial markets and incorporated into mainstream investment portfolios.

Take the notorious derivative of 2008, the “collateralized debt obligation” (CDO). Prima facie, it is a shared investment pool composed of multiple “revenue generating sources” or debt obligations (i.e. student loans, mortgages, health insurance debts, credit card debts), which are combined into “tranches” corresponding to their relative level of “risk,” or the presumed chance of default by the borrower. As the different “tranches” of the pool are filled by the inflow of payments on the debt obligations, investors are permitted to withdraw their shares and collect revenue based on their corresponding level of buy-in. In other words, the initial debt obligations, already a form of interest-bearing or self-valorizing capital, become secondary sites of profit-extraction for the investors, while the initial lender can offload the risk of default on the debt obligations they contract. For instance, if a homeowner defaults on their mortgage payments, the lending body would be collateralized against the losses, which are shared by the CDO investors and ideally offset by the inflow of revenue from other assets in the pool.

In practice, this is anything but the case: as the initial CDO circulates shadow financial markets, the nominally medium-risk ‘middle-tranche’ of assets are dissected and combined with the middle-tranches of other CDOs to form a “CDO-squared” (once recombined, twice removed from initial debt-obligations), which would then undergo further invasive surgery and combination to reemerge as a “CDO-cubed” (twice recombined, three times removed from initial debt obligations), and so on. In the process, the initial debt obligations – especially the “riskier” ones – would often be divided to the nth degree and disseminated across the tranches of many synthetic CDO-offshoots, apparently distributing their risk evenly and making them increasingly undetectable with each new permutation.

Such instruments allow major institutional lenders (e.g. banks, hedge-funds, etc.) to nominally clear their credit-ledgers, thus encouraging predatory or even fraudulent lending practices on the premise that the firms would be protected from the blow-back of their incurred risk by cushioning these loans in apparently secure CDOs. Yet, there’s a peculiar thing that happens when such practices become widespread. As CDOs are traded and combined with other oblique derivative forms (e.g. credit default swaps), the apparently solid ‘bed-rock’ of secure loans falls away – and no one notices, everyone assuming that they are the clever actor in the trade. Moreover, after being submerged into the CDO ‘pool,’ where they are vertiginously divided and recombined, the risk-laden, predatory loan contracts reemerge post festum as seemingly secure, AAA-rated bonds safe for mainstream investment portfolios. Far from being minimized for any individual investor, risk is universalized. Cue 2008, etc.

The first private CDO was issued by Drexel Burnham Lambert to the Imperial Savings and Loans Association in 1987. By 2007, it is estimated that between $386 and 500 billion in CDOs were issued over the prior two years alone, not counting untraceable offshoots in shadow banking markets. At the end of 2009, they accounted for over $542 billion of the nearly $1 trillion dollars lost by financial institutions at the height of the crisis. For their part, Drexel Burnham Lambert would be forced into bankruptcy in 1990 due to regulatory blow-back for illegal practices in the junk bond market, the same year that the Imperial Savings and Loans Association was issued a cease-and-desist order by the Office of Thrift Supervision for “expected unsafe or unsound practices,” before themselves going defunct in 2010. Fast forward to 2023: the market in “collateralized loan obligations” (CLOs), the repackaged and renovated sibling of the CDO, now amounts to almost $1 trillion. So much for regulation.

The meagre attempts at ‘systematically weeding-out financial sophistication’ by regulatory means did not simply fail because of a lack of oversight or enforcement by governmental or intergovernmental bodies, assuming they had any such capacity or interest to do so in the first place. Systematic regulation was undermined from the outset by a systemic process of valorization respecting no bounds. A process which, through the creation of instruments such as the CDO/CLO, continuously invents new social relations as sites of profit-extraction, evading regulation through its extra-legal interstices: not strictly illegal but legally-illegible, since these sites of valorization precede their formalization into law. These attempts were further hijacked by the subsequent, unprecedented accumulation of wealth in the pockets of an unelected minority, cementing a form of economic power eclipsing political power in liberal democracies.

The only caveat that we must add is that this process of valorization now extends beyond the limits of commodity economies narrowly conceived. Financial instruments have become commodities traded across wide geographical expanses with a velocity and frequency that evades human perception or bodily capacity: “TABB Group estimates that if a broker’s electronic trading platform is 5 milliseconds behind the competition, it could lose at least 1% of its flow; that’s $4 million in revenues per millisecond. Up to 10 milliseconds of latency could result in a 10% drop in revenues,” straight from the horse’s mouth.

A central aspect of Marx’s critical revolution was his discovery that ‘socially necessary labour time,’ or the average amount of time it takes to produce a commodity under definite social conditions, plays a determining role in the value of that commodity, not concrete labour time or the actual duration expended by the producer. The value of a croissant, in other words, is not derived from the time taken by my local baker to produce it, but by the average time of all bakers to bake croissants of a similar quality and price at a given moment and in a definite economic context, all things being equal. More precisely, for Marx, value is derived from the ‘surplus’ labour time inversely relative to necessary labour time. But the point remains: the socialization of production by the capitalist economy effects an abstraction of time from the lived, concrete duration of individual work. The working day of my baker is only ‘socially-valid’ or legible as valuable, value-generating labour insofar as it is brought under the aspect of this ‘ideal temporal average,’ which retroactively shapes the conditions of production. Hence the world of difference between my private attempts to bake croissants at home and the socially-valid labour of my cherished baker. And as different bakeries compete to maximize profits vis-à-vis croissant production by introducing new technologies, new techniques or new divisions of tasks, they collectively reduce their socially necessary labour time. The rate of profit-extraction is thus inversely proportional to the time required to bake a single croissant, or to produce a valuable commodity in general. A race to the bottom, in other words, with the zero-point of necessary labour time becoming the orienting ideal in the Kantian ‘regulative’ sense: impossible to realize, but efficacious in shaping the productive activity of society on the whole.

Contemporary finance carries this abstraction and reduction of temporality to its extreme: Marx writes, “if the striving of capital in one direction is circulation without circulation time, it strives in the other direction to give circulation time value” (Grundrisse 659). The circulation time of money, originally an unproductive gap separating the sale and purchase of commodities, presented a real limit to profit-extraction and accumulation. In its present form, finance amounts to the penultimate attempt at overcoming this limit by valorizing circulation time itself. Abstract units of trading time to the tune of nanoseconds become sites of profit-extraction and competition. And, as with my dear baker, this temporal abstraction exercises a real, compelling influence on the behaviour of high-speed stock traders. Our friends at TABB Group remind us, “if a broker is 100 milliseconds slower than the fastest broker, it may as well shut down its FIX engine and become a floor broker”: so very little time for critical self-reflection on their part. As Marx quips, “they do it without knowing it.”

Still from Adam Curtis‘ 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation

‘Real’ subsumption pointed to the reorganization of labour and the intensification of productive forces according to the dictates of profit, valorizing productive relations in the process. Financialization extends this process to socioeconomic life in general, recomposing and creating new relations – new forms of debt obligations, new distributions of risk, even new modulations and retractions of time – as sites for profit-extraction. It commodifies socio-economic life in general, and, in so doing, becomes increasingly detached from the material conditions of life from which value is derived in the first place. In Marxian terms, so-called ‘fictitious‘ capital – fictional in the sense that the derived value of capital is increasingly distant from the production and circulation of ‘real’ commodities – colonizes every sector of the global economy.

In short, financialization becomes ubiquitous, corroding traditional forms of sovereignty and displacing real social sources of value. To repeat, the hypercomplex, global network of economic interdependency engendered by financialization socializes the burden of risk while leaving monetary returns on capital investments under private control. In certain cases like the CDO/CLO, financial instruments are deliberately abstract, since mainstream investors – whether they are individuals, public pension schemes, or sovereign nations – are less likely to question the stability of their investment portfolios if they don’t fully comprehend their manifold risks. But Marx’s point still holds: the generally abstract character of such instruments is the outward form of appearance engendered by an ever-more ubiquitous ensemble of social relations, itself historically determined by the twinned movements of real subsumption and centrifugal financial markets. The latter of which spin out of control as profit-extraction becomes increasingly detached or ‘abstracted’ from commodity production, and circulation time abstracted from their real exchange.

To be clear, this trend was necessitated by the historical tendencies of capitalism described above. Without the widespread expansion of liquid credit or fictitious capital following deindustrialization and the 70s ‘stagflation’ crisis, consumption would have plummeted and developed Western economies would have crashed as real wages stagnated behind inflation, likewise dragging those economies where global commodity production had fled down with them. The kicker, as it were, is that this crisis and the divergence of real wage growth from inflation was precipitated in part by the very process that financialization expresses in its purest form: the expansive, centrifugal movement of capitalist economies effectively realized as the exportation of commodity production from its tradition centres in Western Europe and North America to cheap labour markets in the Global South. A vicious circle of necessitation, in other words, borne out by the inner logic of capital. Finance is not a deviation from ‘pure‘ capitalism, as some right-wing libertarians argue, but a necessity engendered by its real development.

Neoliberal reforms that accompany financialization are not a historically novel phenomena born sui generis. They express this expansive logic animating capital, from its birth to the present era of financialization. And this ‘limitless’ movement is realized in fact as the ‘tearing-down of all boundary-posts and limits,’ most evidently those national and international legal frameworks regulating circulation. Viewed from within, the resulting ‘free’ movement of capital appears to us as the freedom of individuals in the market. Marx writes:

Because competition appears historically as the dissolution of compulsory guild membership, government regulation, internal tariffs and the like within a country, as the lifting of blockades, prohibitions, protection on the world market – because it appears historically, in short, as the negation of the limits and barriers peculiar to the stages of production preceding capital […] this has led at the same time to the even greater absurdity of regarding it as the collision of unfettered individuals who are determined only by their own interests – as the mutual repulsion and attraction of free individuals, and hence as the absolute mode of existence of free individuality in the sphere of consumption and of exchange (Grundrisse 649).

In the ‘inverted world’ of these appearances, the 2008 American mortgage crisis is the result of defaults by ‘irresponsible‘ homeowners, the Greek sovereign debt crisis of ‘lazy‘ workers, or the present French pension crisis of a ‘cavalier‘ national attitude towards labour. Only 48 bankers and 1 politician faced jail-time for the largest economic disaster since 1929, over half in Iceland where all three major banks failed. Meanwhile, publicly-funded bail-out packages to financial institutions and corporations in America alone amount to somewhere from $498 billion to $4.8 trillion and counting, depending on whose numbers you trust. Such calculations prove to be a fool’s errand, remaining particularly vulnerable to the distorting influence of political and ideological interests. Pace Marx, this is not the result of some conspiracy by an elite ‘cabal‘ of bankers but a material effect following from the capitalist mode of production, an effect genetically contained in the fetishism of commodities and money detached from the material conditions of production. It is the logical and ontological, material consequence of the peculiar separation and abstraction effected by capitalist exchange, through which the source of economic wealth diverges from effective utility, value from use-value, and sale from purchase. Already in 1857, Marx warned us: even “in the quality of money as a medium, in the splitting of exchange into two acts, there lies the germ of crises” (Grundrisse 198).

The inner life of finance comprises the domination and impoverishment of real individuals, of living labour. If “the simple forms of exchange value and money latently contain the opposition between labour and capital” (Grundrisse 248), “the contradiction of labour time and circulation time contains the entire doctrine of credit” (648). Financialization meets its own internal limit in its increasing distance from real, social sources of value, as illustrated by the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis. Once this contradiction comes to a head, capitalism requires extra-economic intervention in order to stabilize itself. This can take the form of massive injections of liquidity as with the bail-out packages of 2008, austerity measures as with the current réforme des retraites, or the imposition by force of neoliberal agendas on national economies abroad.

Just ask a Chilean about the very real and very brutal effects of the theoretical abstractions propounded by the Chicago School.

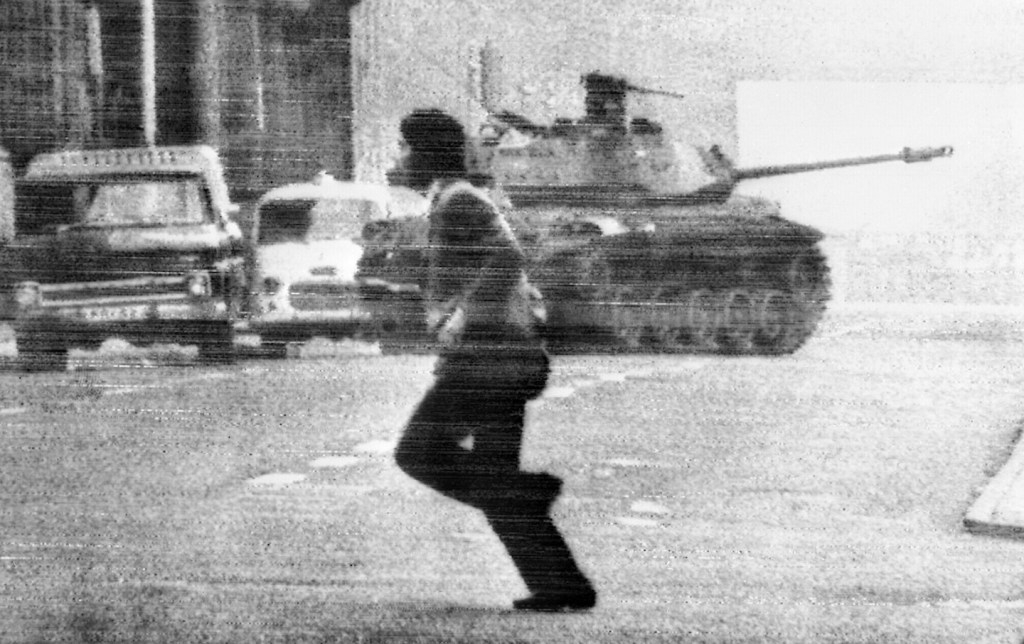

A tank passing Chile’s presidential palace after Pinochet’s anti-Allende coup, abetted by America: 11 September 1973, photo from AFP via Getty Images

crisis & “so-called primitive accumulation”

It should us give pause that Mau excavates one of the most pointed elaborations of capital’s matured form over the course of Marx’s description of the necessary, germinal conditions in which it first began jutting its ‘metabolic’ roots into the soil of social production. Preceding conditions so contrasted in the nudity of their violence to those of economic reproduction that they almost make the latter appear tranquil by comparison. Marx’s point extended beyond the dramatic effect of this comparison. It indicates the paradox of explaining precisely how the capitalist mode of production takes off in the first place. More to the point, it is the question of working out the transitional process through which a class-based division of labour develops before the “mute compulsion” of quasi-natural laws that maintain it fully take hold; that is, how a mass of dispossessed workers is first formed in contradistinction to a class in private ownership of the means of production.

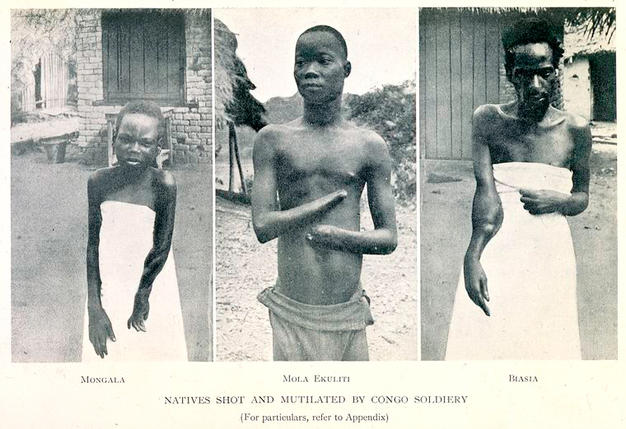

The explanatory paradox – that this constitutive process can’t conform to any outward economic rationality or legal-political logic that it founds and through which it justifies itself, that it must rely on the coercive power of the state, imperialism, colonialism, slavery, and the like – discloses a real contradiction. Capital necessarily presupposes the commodification of labour-power, land, and natural resources while being unable to directly constitute, à la its structuring logic, these necessary quasi-commodities. The Japanese economist Kōzō Uno articulated this problem with concision: “the establishment of a capitalist commodity economy can only come about with the commodification of that which capital itself cannot [directly] produce, namely labour power [to which we can add land and resources]” (Theory of Crisis 44).

Unlike slavery and serfdom, where the whole person of the slave or the whole product of the serf is unilaterally expropriated by the slave master or lord, capitalism requires workers to contract out their labour-power ‘freely’ and for a given period of time to the capitalist. For their part, the capitalist can’t directly force the labourer into production, at least according to their self-justifying rationale. Likewise, before the establishment of capitalist property, land and natural resources exist in common: in order to convert them into property, and therefore into the necessary means of production for a commodity-trading economy, the capitalist cannot fall back on the rationale of apparently ‘free and fair’ exchange or the ideal conditions of the Lockean proviso. Other means are required.

Congolese brutalized by King Leopold II’s colonial rule, murdering 10-15 million from 1885-1908: profits from his plantations established Belgium as an industrial power

In his critique of Adam Smith’s ‘original sin’ of ‘primary accumulation,’ Marx goes to pains to underscore that capitalism was in reality born “dripping head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt” (Capital I 926) by plural and uneven processes of state-assisted, coercive expropriation severing to-be workers from the land and from their subsistence means of reproduction: from enclosure acts and the dissolution of guilds to imperialism, the transatlantic slave trade, and the failure of reconstruction, capital was born out of the excessively violent expropriation of labour, land, and resources. This process served to generate a surplus population of so-called “free workers”: free, however, “in the double sense that they neither form a part of the means of production themselves, as would be the case with slaves, serfs, etc. [thereby free from any direct appropriation of their whole person or their product] nor do they own the means of production [thereby free from, ‘unencumbered by,’ property or capital]” (Capital I 875). Left landless, penniless, and without any access to the means of production, the working class was free to sell its labour or starve. A population with nothing but their own labour-power as a commodity, free to be subsumed by capital and exploited by a germinal bourgeoisie.

Marx’s intention in this chapter is admittedly limited. By critiquing the idyllic origin myths of political economy, he likewise furnishes a possible explanatory ground for the transition to capitalism following his initial, theoretical reconstruction of its structuring logic and internal ‘principle of motion’ during the course of the preceding chapters. However, as observered in the developed form of finance, the original contradiction persists. In capitalist economies, workers can only be indirectly compelled to sell their labour-power: land and natural resources simply exist where they exist, without regard for the needs of capitalist production. A simple ‘act of God’ – say, a pandemic – has the potential to stymy the compelling power of capital over the worker. Likewise, if a nation is unwilling to open foreign access to their natural resources, other means of influence again become necessary. Where Marx cited the ongoing Opium wars exacted against China by Britain as an example of contemporary “primitive accumulation” in Capital, we just need to glance at that little “black book” of American-sponsored coup d’états to get a sense of what these other means look like.

A protest during the American and British-sponsored 1953 Iranian Coup, aka Operation Ajax, deposing Mossadegh following his nationalization of the country’s oil reserves

For Uno, the persistence of this contradiction signalled the proverbial ‘Achilles’ heel‘ of capital. Whether his prognosis was correct will be judged by the cyclical history of capitalist crises, which appear to grow ever more ubiquitous with the increasing distance of ‘fictitious’ or financial capital from the material circumstances of the global majority. Gavin Walker has provided incisive commentary on Uno’s Theory of Crisis, which will be reprinted later this year by Historical Materialism.

Whether the process of “so-called primitive accumulation” itself ended at a specific historical moment or continued in sublimated form is an unsettled question. For my part, I tend towards a reading of ‘ongoing primitive accumulation,’ an admittedly clumsy formulation given that Marx criticized its characterization as both “primitive” – as if it referred to some distant prehistory of capitalism rather than its persistent, dark underbelly in the present – and “accumulative” – since these plural processes of robbery, dispossession or unalloyed coercion en masse operate precisely outside the structuring logic of capitalist accumulation and exploitation. Not “primitive accumulation” but ongoing expropriation alongside exploitation. A process dubbed X2 by Peter Linebaugh: “expropriation is prior to exploitation, yet the two are interdependent. Expropriation not only prepares the ground, so to speak, it [also] intensifies exploitation” (Stop, Thief! 73).

Political scientist Glen Coulthard has followed suit, emphasizing the inner connection drawn through Marx’s account of “primitive accumulation” between the “totalizing power of capital [and] that of colonialism through ‘originary’ dispossession,” recasting such dispossession as an “ongoing, constitutive feature of settler-colonial states, like Canada.” He is correct to do so, with an important clarification. Since the ongoing necessity of extra-economic coercion is engendered by a real contradiction of capitalist reproduction itself, pace Rosa Luxembourg, it is not only manifest on the peripheries of imperialism or the heartlands of settler colonialism. It rears its head even in the metropoles of the old European powers such as France, at those critical junctures when the capital’s automaticity and mute compulsion shore up. Achilles folds.

The mature abstractions of capital shelter real, historically determined relations of domination – relations that are reproduced through a form of economic power unique to capitalism, as Mau shows with versatility. Yet, once threatened, this reproductive economic power just as soon sheds its mask of respectability and regresses into the violence out of which it grew, as witnessed during the gilets jaunes or currently in the streets of Paris and at the eco-blockade in Sainte-Soline – the latter of which saw the police fire a grenade every two seconds for two hours and left two activists fighting for their lives.

reading capital as natural history

Portrait of an ecological militant at Sainte-Soline, photo by Arthur Perrin

Marx comments, with a biting note of irony, in the first preface to Capital I:

I do not by any means depict the capitalist and the landowner in rosy colours. But individuals are dealt with here only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, the bearers of particular class-relations and interests. My standpoint, from which the development of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he [sic] remains, socially speaking, however much he may subjectively raise himself [sic] above them. (Capital I 92)

If ‘nature is the human’s inorganic body insofar as it is not itself a human body,’ then the assertion that humanity’s “physical and spiritual life is linked to nature means simply that nature is linked to itself, for [the human] is a part of nature” (MECW 276). Capitalism, however, posits ‘the separation between these inorganic conditions of human existence and its active existence.’ Capital, that is, really engenders the semblance of two separate realms: our social, economic lives on the one hand and our finite ‘inorganic’ constitution on the other. Thus, two separate and mirrored states of existence: the inner compulsion animating the relations of production and dependance in the one adopting the appearance of law-like necessity animating the other.

Spinoza once argued that the supposition of teleological purposiveness in ‘Deus sive Natura‘ [God or nature] was the illusion of a specifically human form of prejudice. The projection, that is, of the human being’s own presumption to act purposively towards apparent final ends, when we are in fact necessarily moved by conatus or a sheer, impersonal striving to preserve and augment one’s existence. The pathological dimension of this projection rests in our thoroughgoing ignorance of this necessity, specifically the necessity of action taken in the double genitive: action as both necessarily determined and demanded by conatus. Spinoza’s critique of teleology was thus not only directed at an anthropomorphized ‘Deus sive Natura.’ It was directed at humanity itself, at the ‘fetishized’ specular image that we construct for ourselves in “nature” out of the ignorance of our own nature. Marx would concur, with the salient caveat that this separation doesn’t merely reflect the alienation of the human from some quintessential “species-essence,” as he once asserted in the 1844 manuscripts.

Rather, capital posits the very distinction between the ‘form’ (the world of money and commodities) and the ‘matter’ (living labour and resources) of life, between two apparently distinct social and natural “essences.” Pace Spinoza, it furnishes the very appearance of something like a generic “human essence” or “nature” independent of our social and historical condition, one smuggled back into the practical illusions of economics as though it were timeless fact. Spinoza swept away our presumption of the purposeful will by treating individuals as constellations and concretions of an impersonal conatus. Marx followed suit, deigning to treat the ‘individual as a personification of economic categories,’ or as the “bearer” [Träger] of “particular class relations,” in the same sense that a beam ‘bears’ or ‘carries’ the weight of a bridge or, saliently, a politician ought to ‘bear’ without prejudice the will their electorate (belying the caricature of contemporary liberal democracy).

‘The capitalist and the landowner’ are but the differentia specifica ’embodying’ the genera of capitalist conatus, the ‘limitless’ self-valorization of value expressed by Marx’s general formula for capital M-C-M’: “value is here the subject of a process in which, while constantly assuming the form in turn of money [M] and commodities [C], it changes its own magnitude, throws off surplus-value [M’] from itself considered as original value [M], and thus valorizes itself independently […] It brings forth living offspring, or at least lays golden eggs” (Capital I 254). The linear augmentation of value vis-à-vis the conversion of money and commodities is, in fact, a circle, and a vicious one at that. Vertiginous in its apparently groundless gravitational force.

In Book I of Spinoza’s Ethics, the purposeless inner necessity engendered by Euclidean proofs offers a rational counterweight to our teleological pathology, mathematics expressing the inner necessitation of nature animating the order and connection of thought sub specie aeternitatis (under the aspect of eternity). Marx, by contrast, could not take repose in a pure space of geometry outside of time. The critique of capitalism in its increasingly autonomous and impersonal form demands instead the immanent dissolution of the inner necessity with which it appears to act through individuals. As above, it involves the construction not of a ‘prehistory‘ but rather a ‘natural history‘ of capital, excavating the material processes by which it really subsumes and recomposes that ‘inorganic body’ in which the human is thoroughly submerged. To read capital as ‘natural history’ therefore does not treat nature as the ‘arche-Other’ of society, even less as a paragon of tranquil cohabitation among individuals à la Rousseau or an unbridled war of all against all a là Hobbes. It indicates instead a ‘long and tormented historical development’ marked by the struggle of competition over subsistence conditions or relative dominance. An inner ‘evolutionary‘ compulsion or drive which ‘assumes the form’ of this or that ‘species’ while dispensing with them in turn. A history of struggle and disaster literally encoded in genetics, which Marx discovers in the very DNA of the capitalist mode of production starting out from its ‘birth-pangs’ in “so-called primitive accumulation.”

Capital’s inner, ‘conative’ compulsion is redoubled or, more accurately, redoubles itself back onto the ‘inorganic body’ of so-called nature. That is, it is both effected by and effects real transformations in our natural, physical constitution, evinced by the recalcitrance of the industrial division of labour on agricultural production. The capitalist mode of production, he explains, “collects the population together in great centres, and causes the urban population to achieve an ever growing preponderance,” resulting on the one hand in the increasing concentration of “the historical [‘economic‘] motive power of society; on the other hand, [disturbing] the metabolic interaction between man [sic] and the earth” (Capital I 637). The nominal autonomy of capital’s motive economic force is materialized in the real separation of society’s dominant productive forces from their natural conditions, most importantly that terre ferme out of which they draw sustenance: “all progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is a progress towards ruining the more long- lasting sources of that fertility” (Capital I 638).

A farm about to be enveloped by a dust storm during the great Dust Bowl of the 1930s: photo by Corbis via Getty Images

The densely rich and fertile matter of Marx’s reading of economics as ‘natural history’ is underscored by the references to the couched ‘metabolic‘ structures of labour and production scattered across his late critical work. The ‘real abstractions’ of capital are nothing if not articulations of energetic and relational transformations among bodies acting in concert. Social and communicative processes of coproduction altering and augmenting their power in tandem. Transformations which, moreover, reflect and effect changes in the physical composition of the individual (one needn’t be a Foucault specialist to recognize the influence of the pharmaceutical industry on the body) and their milieu (the manifold ecological and climate crises need no introduction). So many social relations of interchange and interdependence as articulations of material, environmental revolutions enacted historically by the development of productive forces. Despite their ideological disarticulation ‘sub specie capitis‘ [under the aspect of capital], the economic and the biological or ecological are in fact wedded at their origin. Crisis in one begets, albeit in displaced form, catastrophe in the other. Kohei Saito has expounded on this ‘metabolic rift’ and Marx’s enduring relevance for constructing an eco-socialist alternative, to popular acclaim in Japan and abroad.

France’s pension crisis puts the collision course of capital with the natural limits of production in full sight. “Economic growth” and “financial stability” are realized in fact as the ever-intensifying demand on French labour to extend their working lives and increase their productivity, despite obstinate stagnation in real wage growth. In Arkansas, this is expressed more dramatically by the right-wing push to weaken legal regulations on child labour, even in high-risk manufacturing or meat-packing positions. At the same time, America’s ongoing doubling-back on the right to abortion belies the demand to replenish society’s reserve of surplus labour-power, a demand hidden under the thinly-veiled moralism of “pro-life” rhetoric. Not truly pro-life but pro-production, pro-economic reproduction. And the ongoing, private expropriation of the earth’s finite resources continues unabated, despite the catastrophic consequences of extractive industries for our very continued survival as a species.

Yet, according to the financial rationale governing assessments of “risk” against “return,” these natural limits of labour and resources appear as mere “externalities” to quarterly profit margins and dividends. To repeat, Marx offers us the critical clarity to recognize that this trend isn’t a mere deviation from the normal course to be corrected with better regulatory frameworks, but follows logically from capitalism itself. It follows from the ever more precarious detachment of the motive demands of economic reproduction from our actually finite, natural existence. Everywhere, a war of capital against its limits, effectively realized as the simultaneous valorization and denigration of the human, the nonhuman, and the earth alike. Far from anthropomorphizing nature, Marx’s critique serves to precisely denature the economy by belying its mythical, self-justifying origin and apparent force of necessity. No pure “state of nature” as dreamt by the romantics: hence, no pure “state of the market” as postulated by the political economists and continued today by the dominant trend of neoclassical economics.

the janus-face of capitalist reproduction

If a conclusion can be drawn from Macron’s prospective political fate (which is, truthfully, still yet to be seen), it might very well be that, given the optimal admixture of sociopolitical crisis with a historically revolutionary population, the unreason engendered by capitalist reproduction renders neoliberal politicians into their own worst enemies, as the saying goes. By symbolically placing Macron exclusively at the centre of our critical sight-finders and in the spotlight of popular vitriol, we not only risk redoubling the perverse sense of tragic necessity out of which he claims to act, as if he were Antigone: charged with enforcing the antediluvian laws of the economy against to the terrestrial order of democracy. We also risk redoubling the ideological guise in which capital’s “mute compulsion” is draped, diverting our critical and revolutionary acumen away from the ‘real’ cause of the present social, ecological, political, economic, etc., downward spiral. For his part, Macron’s strictly political function remains a ‘differentia specifica‘ of economic power, an appendage to the impersonal, “automatic subject” (Capital I 255) of capital – one that may very well consume him in the drive for limitless self-valorization. On n’a toujours pas coupé la tête du roi.

We would do ourselves a favour to extend our gaze beyond the immediate horizon of this crisis. Capital will likely survive, but to what extent and with what strength in France will depend on the critical breadth and acuity of the labour movement alongside the progressive coalition of social forces in opposition. Needless to say, an electoral success by Le Pen and a corollary social success for the regressive, specifically ethno-nativist face of French nationalism would not only be a half-century step backwards. It would sustain and intensify capital’s stranglehold on social reproduction. Cue Le Pen’s “alternative proposal” to the réforme des retraites, consisting in an increase of social benefits for French families with newborn children, the so-called “good babies” and “good contributors” in her own thinly-euphemistic words. By effectively tying the national “birth-rate” to social productivity, Le Pen’s proposal continues FN‘s historic, anti-immigrant and pseudo-eugenicist “pro-birth” rhetoric, while linking it with the maintenance of social security alongside the reproduction of labour – thus repeating the very demographic reasoning behind Macron’s explicit justifications for the measures.

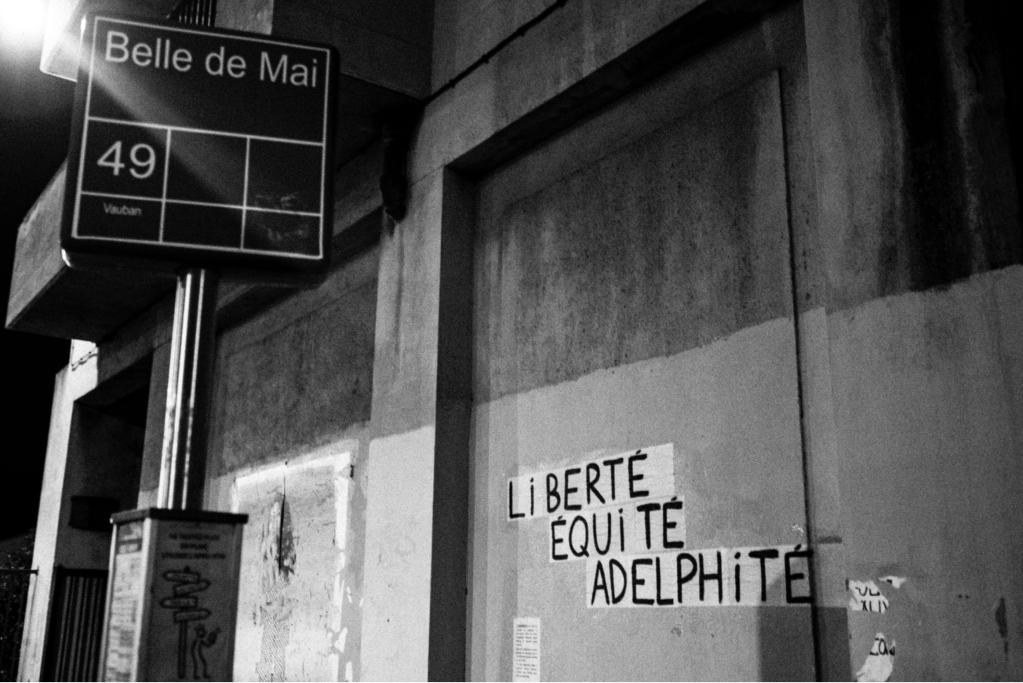

More troubling still, this demographic reasoning draws a conspicuous line of necessity between the aggregate reproduction of the labour force and biological reproduction or birth, threatening to double down on the specific oppression of ‘female’ bodies (in the specific sense of those bodies presently capable of biological reproduction) by capital. Despite the fever-dream shared by some among the accelerationist camp of capital untethered from the human, this intimate ideological link between birth and labour, alongside the corollary form of gendered oppression, is demanded by the ‘mute’ reproduction of capital as long as self-valorizing value is parasitically wedded to ‘living labour.’

The form of labour specific to giving birth is then subsumed by capital. The uterus tacitly becomes an integral part of the means of economic reproduction. “Among all the organs of the body, the uterus is probably the one that, historically, has been the subject of the most relentless political and economic expropriation,” Paul B. Preciado reminds us: “the uterus is the Capitol of biopolitics, the very seat of reproductive power.” We might add that it is the very capital of capitalism, one of the focal points of economic as well biopolitical struggle. Along with their pathological fear of the emigrant other, the “pro-birth” programmes of Le Pen or Orbán share with the anti-abortion crusaders of America complicity in capital’s expropriation of the uterus as the space of economic as well as biological reproduction. From the other end of the durée de vie, the current pension crisis rends this complicity open for all to witness, confirming what the Feminist Marxists affiliated with Social Reproduction Theory have argued for some time.

“Liberty, Equity, Adelphity!” Collage Feministe in Paris

One can therefore sense the ‘mute compulsion’ of capitalist reproduction on both sides of the Macron-Le Pen binary, under the mask of neoliberal republicanism on the one side and of nativist populism on the other. By “flexibilizing” labour and promoting the “free” movement of capital through a multi-pronged attack on social security, labour law, and progressive taxation; or by encouraging national population growth through reactionary, nativist rhetoric and social policies; both political projects ultimately serve to reproduce a future generation of so-called “free workers.” Free, precisely, to continue to be subsumed and exploited, free to reproduce the structural domination of ‘dead’ over ‘living’ labour. Despite their superficial claims to act in the interest of future generations, the programmes of both Macron and Le Pen in reality serve to ensure the continued survival of capital. This fact is not lost on the many thousands of youth, from les lycéens to university students, at the avant-garde of this year’s social upheaval.

“Sovereignty of the producers over production – here is a slogan with appeal, and well beyond the working class, those most directly concerned,” Frédéric Lordon declares. The ultimatum of Marx’s communist hypothesis holds true even today: there cannot be a progressive political force that does not place at the cortège of its struggle the democratic sovereignty of people over their real conditions of production and reproduction, in the most expansive form. This banner of reproductive sovereignty must not be a regulative idea in the Kantian sense, orienting us in principle while itself remaining practically unrealizable. Rather, it must be our concrete and imminent horizon. What does this mean? It means supporting the mobilization and self-organization of labour against their usurpation by a detached managerial, political, and financial strata. It means dropping any residual illusions that collective labour bargaining will ever take place as if among equal parties under present conditions. It therefore means not only establishing a rapport de force with the state and its private benefactors. It means aiming for their full dissolution in present form and their recomposition around the popular interest of their social stakeholders. Namely, all those effected by these social institutions, as opposed to the dividends appropriated and apportioned among a minority of shareholders, or those who already control substantial capital and consequently wield undemocratic, economic power. It means unconditionally affirming the right of metropolitan inhabitants to their cities and homes, against the unabated expropriation of the metropole by anonymous multibillionaires and the infinitesimal ‘Matryoshka dolls’ of their shell companies. It means unconditionally demanding the sovereignty of the form of labour specific to biological reproduction or pregnancy, against those reactionary forces who work to expropriate the bodies and the uteruses of women. It means upholding the demand for recognition by undocumented labourers, thereby affirming their claim to social production writ large. It means taking back the struggle against the bureaucratic state and financialization which corrode democratic and personal sovereignty from without, a cause which has been surreptitiously usurped by the libertarian right and amputated from the conjoined struggle for the economic sovereignty of workers.

So long as the reproduction of capital’s self-valorizing ‘subject’ remains a parasite on society’s productive and ‘incorporeal’ body, in spite of its impersonal and necessary appearances, these manifold sites of reproduction remain the privileged axes of resistance. The present struggle of French labour for sovereignty over their working lives is no different, and deserves our unconditional support.

The task now lies in posing another world to the present one: a world latently taking shape among protestors and strikers in the demonstrations, on the blockades, and behind the picket-lines throughout France. Not a world beyond the present moment, to be sure – no ontological dualism is implied here – but one borne out by these affective encounters which consciously resist capture by capitalist reproduction and its obverse in the coercive state apparatus. To borrow a Spinozist turn of phrase much loved by the French from Deleuze to Lordon, we still don’t know what a political body can do. The present moment is fecund.